Components for weather satellites, unmanned cargo spacecraft and manned NASA space missions: the whole world comes to Bradford Engineering for these items.

They manufacture components for satellites, and manned and interplanetary space missions. NASA, ESA and JAXA are regular customers. André Kuipers also praised their products from his vantage point, thousands of kilometres away in space. A visit to Bradford. “It's a shame you can't actually visit your customers.”

The BepiColombo lifted off for its flight to Mercury in October 2018. The European Space Agency's unmanned space mission will not reach the planet and enter orbit for another seven years. When it gets there, its purpose is to record scientific data under the most extreme conditions imaginable for at least a year. Mercury is the planet closest to the sun. During the day, the temperature can rise to four hundred degrees on this small planet, only to plummet to 170 degrees below zero at night. That fluctuation subjects each and every component of the BepiColombo to extreme stress. Which is exactly why the European Space Agency contacted Bradford Engineering in Heerle (close to Roosendaal).

“We built four reaction wheels for the BepiColombo, which is the ESA's cornerstone mission to Mercury. They help the satellite stay on course with pinpoint accuracy,” says Erwin van der Kroon, Programme Manager at Bradford Engineering. “One of the main challenges is the enormous gravitational pull of the sun, which makes it difficult to put a spacecraft in a stable orbit around Mercury.” The bearings used in the reaction wheels - a tiny but hugely important detail - are a crucial ingredient for the success of the mission and the quality of the scientific readings. Because they have to operate with flawless precision and without vibration for more than ten years without any form of maintenance. That requires the ultimate in precision engineering, because you can't just send a mechanic into space.“

The BepiColombo uses an ion drive, powered by xenon, a noble gas, for propulsion,” says Van der Kroon. Bradford also supplied the technology for controlling and managing the gas supply to the ion drives. “Thanks to our technology, the satellite uses the gas extremely efficiently, so you don’t have to worry that it will ‘run dry’ on the way and get stranded somewhere in space.”

Components for weather satellites, unmanned cargo spacecraft, the ISS and manned space missions organised by both NASA and ESA. The whole world sources these items from Heerle, a town alongside the A58 motorway, near Bergen op Zoom. Two milk cans - Kobus and Kwiebus - that tower several metres high in one of the fields immediately catch the eye. They are a reminder of the town's former dairy industry.

“This was once a wealthy farming community”, says Van der Kroon. He agrees that pioneering aerospace technology and Heerle is an unlikely combination. He lived just around the corner from the company for many years, he says, close to Halsteren, but never heard anybody talk about Bradford, let alone the products they made there. A friend from college drew the company to his attention in 1999. Van der Kroon had absolutely no previous interest in space travel. Star Trek, Star Wars, Wubbo Ockels, the launch of the first Space Shuttle: it all happened without really catching his attention. But he soon became infected by the space virus. Nothing could be more logical. Using your passion for electrical engineering to create products for astronauts, that's definitely more inspiring than working on fire alarm systems for blocks of flats.

Even so, Bradford Engineering is closely linked to the town. It all started with Janssen in Bergen op Zoom, a company that built machinery. Janssen won a contract for work at the Kalkar nuclear power station. But the factory went bankrupt in 1983 and the deputy director of the time was asked if he would complete the Kalkar assignment. He agreed to take on the work and started looking for a suitable factory site. He soon found a good site in the village of Putte, close to the border. An empty sock factory, that had traded under the name of Bradford until the production activities moved to the other side of the border. He liked Bradford as a name: it had a good international ring to it and, as an added bonus, the road in front of the factory was called ‘Bradfordstraat’. So Bradford Engineering was born.

The business flourished. Until the catastrophic Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the mid-1980s. The government withdrew from the Kalkar project soon after. Bradford was forced to shift its focus away from nuclear activities to other industries that use high tech machinery made to unusual specifications, exacting standards and incredibly demanding safety requirements. The Ministry of Economic Affairs put Bradford in touch with the European Space Agency (ESA). There was an instant click. Initially, Bradford was mainly involved in assembly work for instruments for manned space travel. That all changed when the ESA completed an engineering design study for a glovebox in 1988. A partially transparent, box-sized, mini laboratory where astronauts could safely perform research experiments. With gloves fitted to the front and sides to allow handling. Van der Kroon: “Our competitors didn’t see any money in making those gloveboxes. Our managing director of the time did.”

That turned out to be a clever move. Since 1986, Bradford has designed and produced more than fifteen of these gloveboxes. The company has become the acknowledged space glovebox specialist worldwide. They are on the equipment manifest for each and every manned spacecraft mission: the space shuttles, the Russian MIR space station and the ISS. Van der Kroon: “It takes anywhere from two to seven years to develop a box like this. And each one is a million-dollar project.” The biggest challenge in glovebox production is safety. Nothing - not the tiniest whiff of gas or droplet of liquid- should be allowed to escape the glovebox. And if a leak occurs, filters ensure that all the air is purified before it leaves the glovebox. “We do more than just develop the hardware. For example, we also have a service contract for maintenance and spare parts. And we support preparation of all glovebox experiments on behalf of the European Space Research and Technology Center (ESTEC).”

The obvious question is burning on everyone's lips. Did ‘our’ André Kuipers also work with a Bradford glovebox? Van der Kroon smiles. ‘Just a second’, he says. He quickly searches his computer and finds the photo that Kuipers tweeted back to Earth from space in January 2012, during his ISS mission. Along with his comment: ‘After 7.5 years, it's great to work with Bradford's Microgravity Science Glovebox again’. It is a memorable picture: tubs hang weightlessly from the MSG box. The box was developed for eight years before it was launched in 2001. Kuipers received a presentation from Bradford subsequently. Van der Kroon proudly says: “I worked on this glovebox between 1999 and 2002. The electronics are my work. A picture like this always gives you a kick. Our work here in Brabant will go down in the history books as a fantastic achievement.”

In 2004, the MSG was followed by the Life Sciences Glovebox (LSG). The largest glovebox ever at 450 litres, this product was developed for the ISS. It was waiting on the side lines until last year, Van der Kroon tells us. An unmanned HTV-7 spacecraft took it up to the ISS space station. The astronauts couldn’t wait to unpack their latest gift and install it in the Japanese experimental module in the International Space Station. Understandably so, in Van der Kroon’s opinion, because that LSG is really something. Because of the large front window, which can easily be removed. And because two astronauts can use it at the same time. The LSG also takes some of the load off the station’s MSG, which had previously been upgraded in 2017 when the fixed window was replaced by a removable transparent panel. “Incredible but true: the MSG on the ISS has already clocked up more than 43,000 operating hours. It is the most intensively used item of scientific equipment on the space station.”

Bradford moved away from Putte in 1997. The factory was located in the middle of the village, next to the church, and had no room to expand. Their new facility, a former kitchen factory, is about 30 kilometres away in Heerle. A total of 2000 square metres, production and office space, several buildings, including a clean room where 80 specialists work to the highest quality standards. “The aerospace industry is a rather conventional sector”, says Van der Kroon. “Product development, which can take up to five years, involves several rounds of rigorous testing.” This is perfectly understandable: everything inside and outside the ship must have a long service life. If something breaks down on the way, you can't just fly in a mechanic. Attracting new employees to this rather remote part of the world is just as challenging. Very different from America, where people queue up for jobs in the aerospace industry. “We are much more down to earth here. Space travel is not something that people identify with in the Netherlands”.

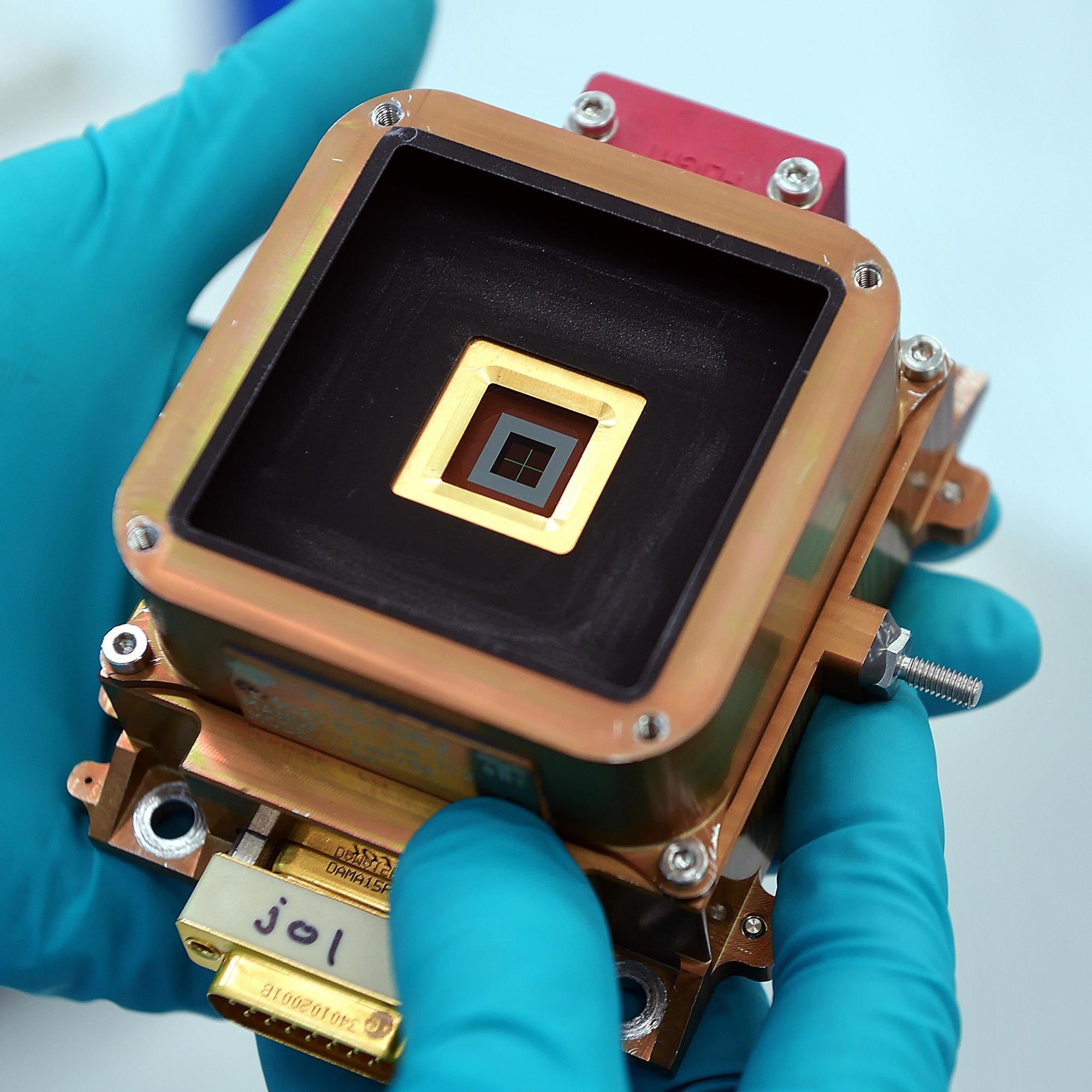

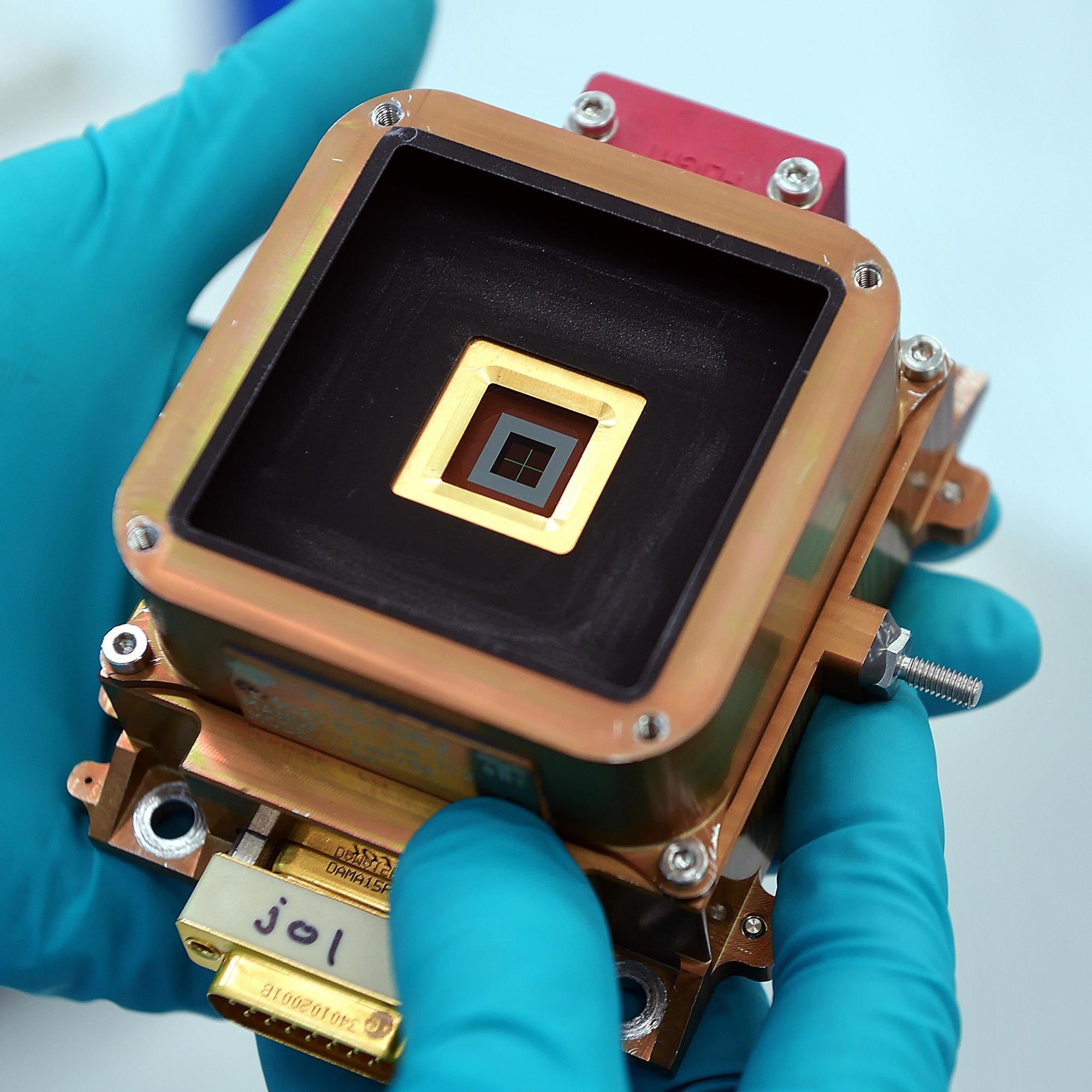

The year 2003 started with a disaster. The space shuttle, Colombia, broke up on re-entry. All seven astronauts were killed. As a result, all missions were put on hold and the orders for gloveboxes dried up. Bradford had to shift its focus yet again. The company switched to making components for the satellite market. Fortunately, they had started developing this activity in 1994. An example of great foresight because the time-to-market for new products in this field is 10 to 15 years on average. “We understood the wisdom of reducing our dependence on manned space travel as far back as the beginning of the nineties. We were making instruments that lasted pretty much forever and there was no real need for replacement. So we were dependent on market growth just to maintain our sales. And that growth potential was and is very limited. After all, there is only one ISS. On the other hand, the satellite market showed strong growth back then and continues to do so.” Today, Bradford is the market leader in Europe for most satellite components. Sun sensors that measure the satellite’s position relative to the sun. Reaction wheels that control the satellite’s position. And propulsion-related systems such as level gauges, pressure transducers, flow meters, and control and switching valves that ensure that a satellite reaches and stays in the right orbit around the Earth: “These products are used for most European space missions.”

Bradford also started to develop products for the commercial satellite and space industry in 1994. “We saw that manned spaceflight was going into decline. The government was increasingly withdrawing support," says Van der Kroon. This has created opportunities for new commercial players and start-ups that send missions and satellites into space independently. This development will almost certainly play a major role in Bradford's future. “We are used to producing custom components at the moment. However, commercial companies buy off-the-shelf components. We recently built a batch of sun sensors for a large number of new satellites for one of these new players. A significant order, but the unit prices are nothing like what we charge for ESA missions.” He also sees potential in the network of satellites that will soon orbit the earth in mega-constellations in order to provide ultra-fast internet. They are closer to the atmosphere, have a shorter life span and are therefore made to a different price. “We focus on quality. If you are used to making a Rolls Royce, suddenly switching to making a Fiat is challenging. You have to adopt a different approach. And the parts are different as well.”

In 2016, Bradford was acquired by the American AIAC, the American Industrial Acquisition Corporation. This American investor has a passion for aerospace. The Americans encouraged Bradford to go on the acquisition warpath. Van der Kroon: “Our work is not only technically complicated. The same applies to the political and financial aspects. Because the Netherlands invests relatively little money in ESA projects, Dutch companies are only eligible for a small slice of the ESA pie. That's why our growth strategy focuses on acquiring companies in other parts of the world. To ensure access to the European development budget and expand our product range.” A Swedish company that manufactures non-toxic drive systems for spacecraft was one of the businesses that Bradford snapped up. “We make everything between the fuel tank and rocket drive, so the fit was excellent.” The acquisition cost a pretty penny, but was definitely worthwhile. "We could have developed a drive system like this in house. But you still have to wait and see if it operates properly. The acquisition turned us into a global player in this niche market overnight, and doubled our turnover."

“Just look up at the sky”, says Van der Kroon. Currently, 2004 Bradford products are orbiting the globe. Hardly anyone knows this. “You can't see what we make. Sometimes, not being able to drop in on your customers for a quick visit is a disadvantage”. Personally, he would love to go on a tour through space. The weightlessness, and hovering effortlessly. But then there’s the downside: nine months of preparation, and horrific stories about space sickness and what the G-forces do to your body during a launch, “No, I prefer keeping both feet firmly on the ground.”

You can copy the full text of this story for free at the touch of a button